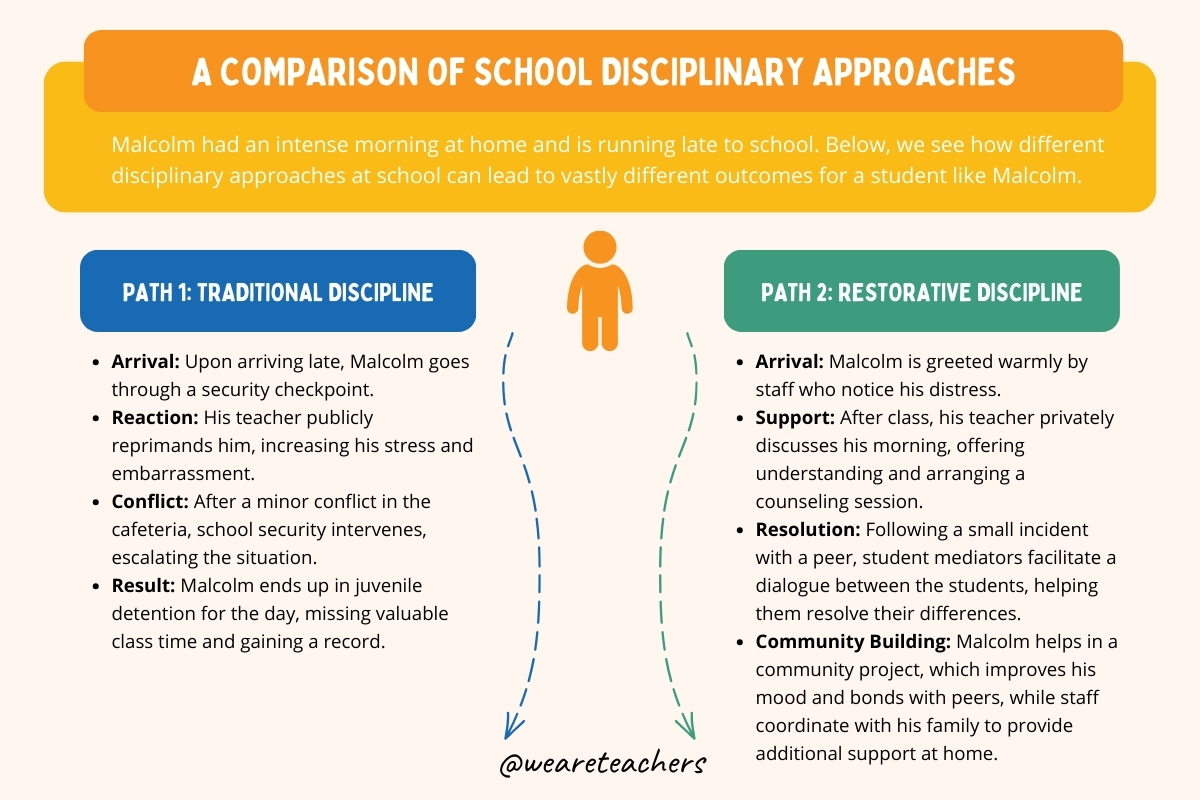

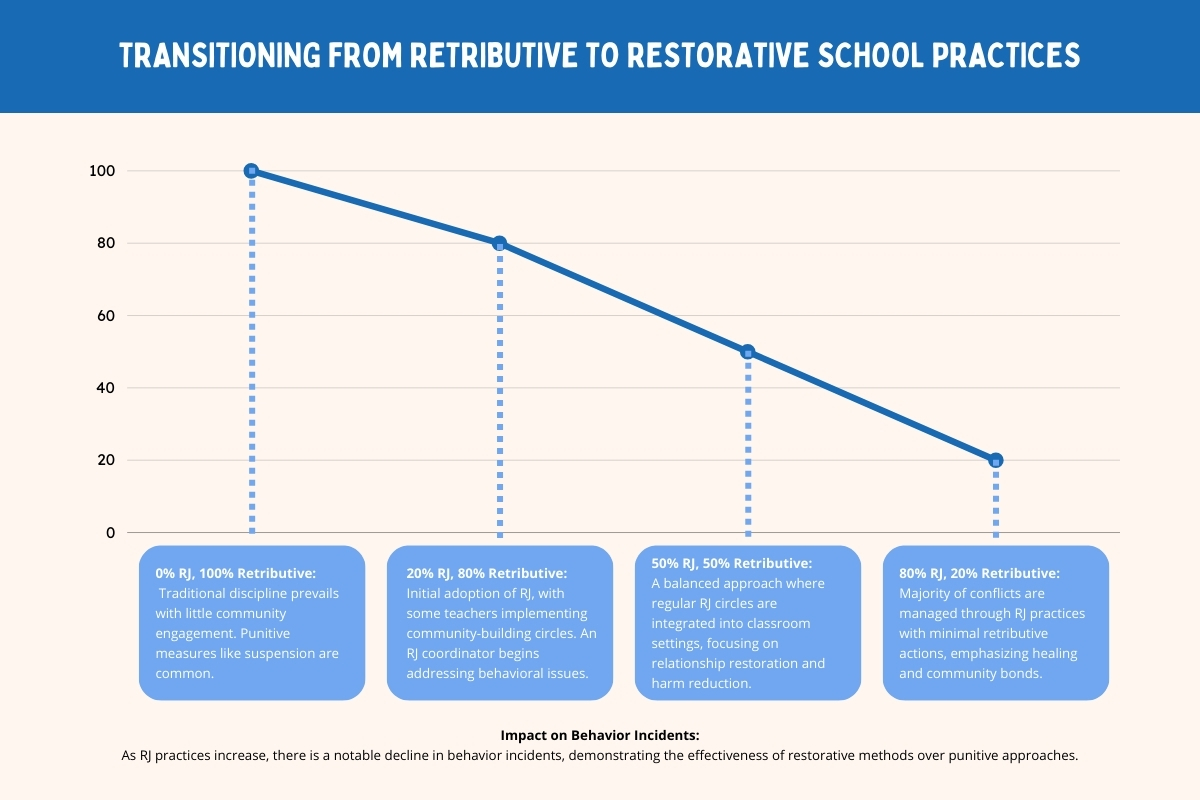

In traditional school settings, discipline often follows a punitive model: Break a rule and face consequences like detention or suspension. While this approach aims to deter misconduct, it frequently interrupts students’ education and may inadvertently lead to repeated behavioral issues without addressing the underlying causes. These conventional methods often fail to equip students with necessary conflict-resolution skills. As a result, a growing number of educational institutions are shifting toward a more holistic approach known as restorative justice. This innovative model focuses on healing, responsibility, and the rebuilding of relationships, offering a more sustainable solution to school discipline.

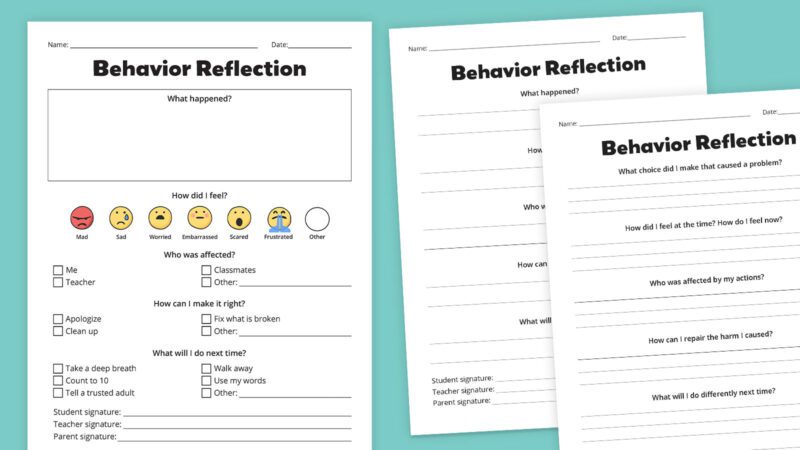

FREE PRINTABLE

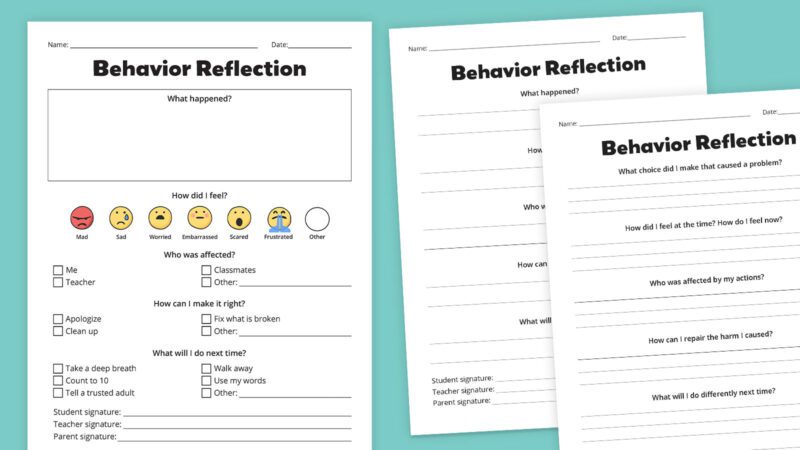

Behavior Reflection Sheets

Behavior reflection sheets are a fantastic tool to use for restorative justice. We created this behavior reflection sheet bundle with six different options so you can choose what works for you and your students.

What is restorative justice in schools?

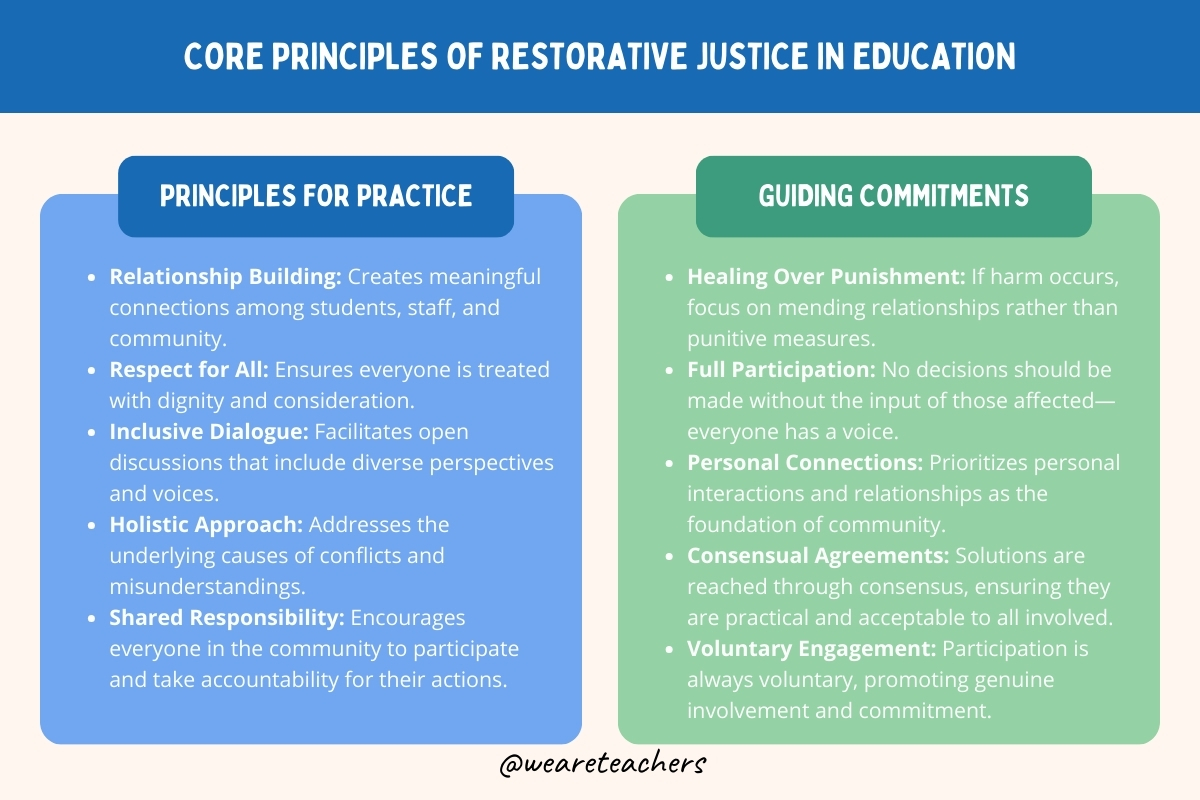

Restorative justice in schools represents a transformative approach to discipline that focuses on repairing harm and rebuilding relationships rather than punishing students for misbehavior. This practice is based on principles of empathy, respect, and accountability, encouraging students to understand the impact of their actions, take responsibility, and actively participate in the healing process.

The goal of restorative justice is to “build community and repair relationships while supporting reflection, communication, and problem-solving skills for staff and students,” which can lead to more effective learning and teaching. It emphasizes dialogue and mutual agreement, involving all parties affected by a conflict—including victims, offenders, and the wider school community—to address issues collaboratively.

By shifting from a punitive model to one that seeks to understand and resolve the root causes of behavior, schools implementing restorative justice report significant reductions in suspensions, improved student behavior, and better overall school climate. This approach not only helps in managing individual incidents of misconduct but also fosters a culture of care, respect, and community, essential for educational success and social development.

“At its core, restorative justice is about how the humans in the building relate to each other—what to do when there is a breach or a break, and how to repair,” says Beth Napleton, founder of a middle and high school on the far South Side of Chicago. “In many cases, this can be a massive paradigm shift that changes the foundation of the school. … There’s a lot of work that goes into this—this is a true change management initiative, and it takes time. Sometimes it may progress more slowly than you would like, but the journey of 1,000 miles starts with a single step.”

What are the basic practices of restorative justice?

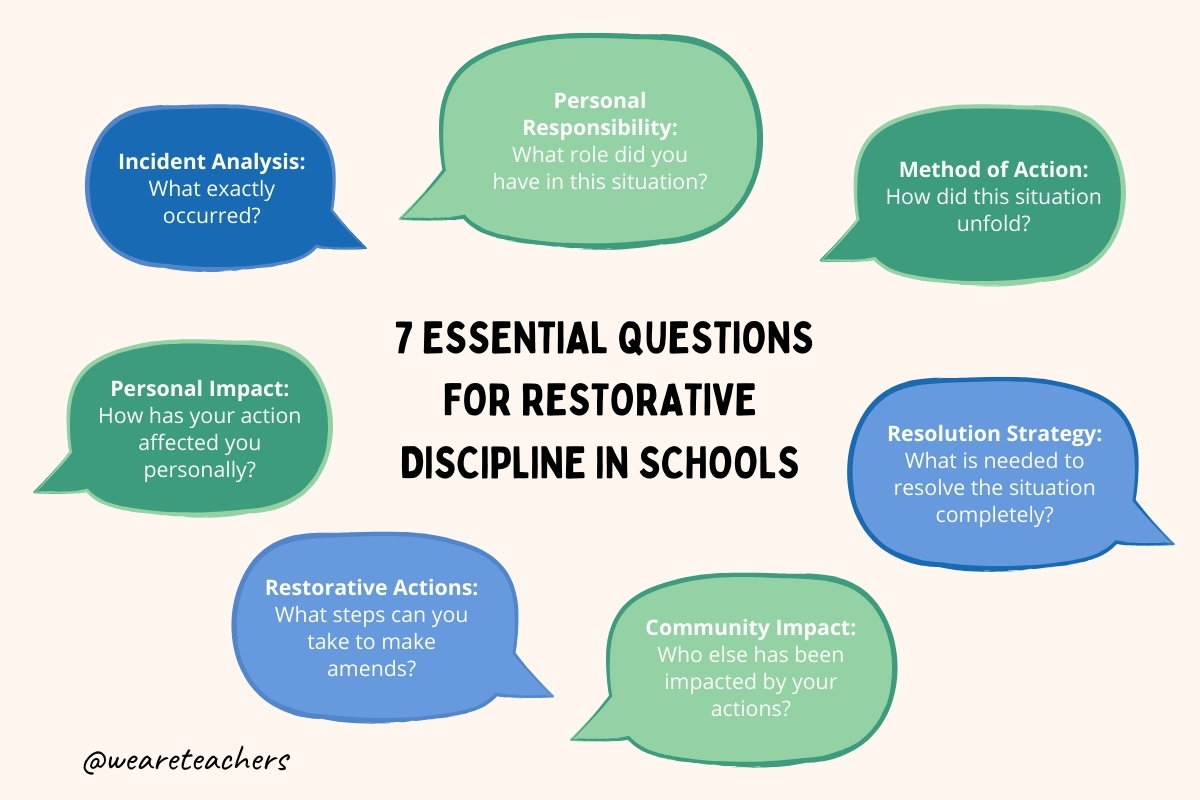

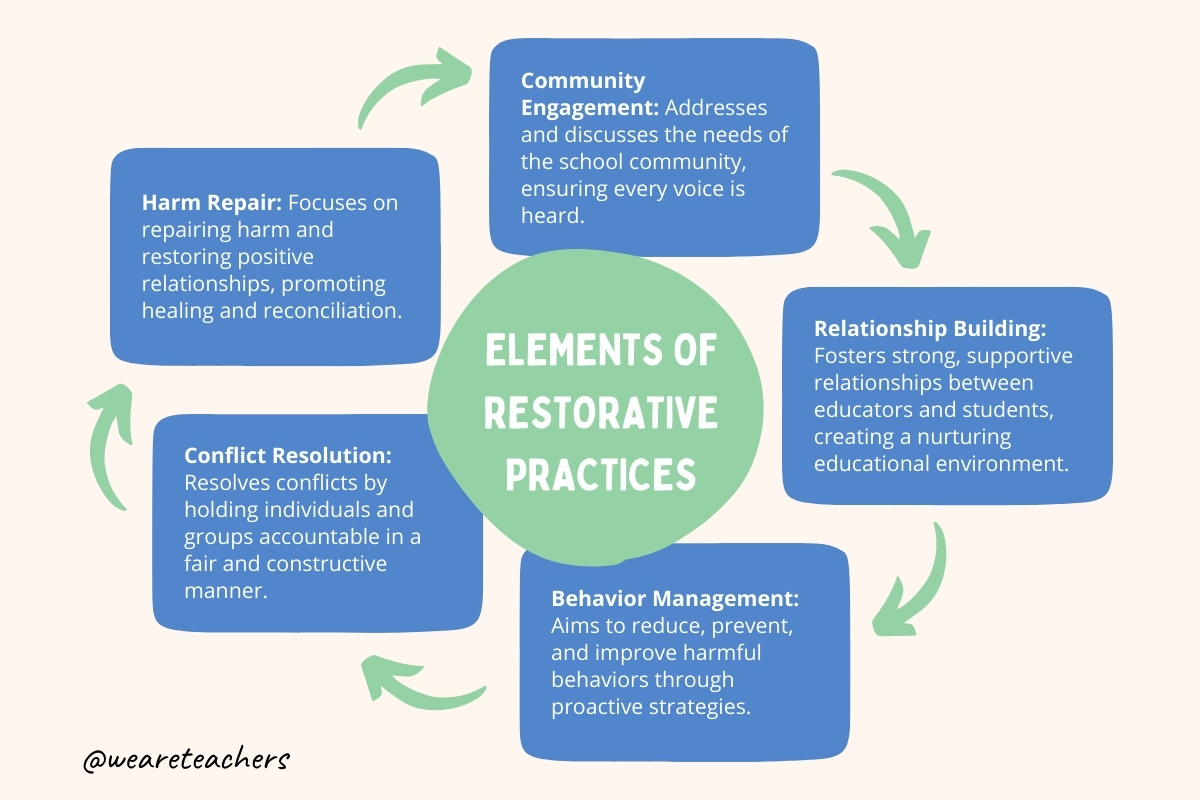

Restorative justice is centered on a set of practices that aim to mend the harm caused by an incident and rebuild relationships among those involved. Here are some foundational practices typically employed in restorative justice frameworks:

- Facilitated dialogues: These are structured conversations, often referred to as “circles,” where all affected parties gather to discuss the incident. The process is guided by a facilitator who ensures that the dialogue is constructive and respectful.

- Conflict resolution: This involves direct engagement between the offender and the victim, allowing both parties to express their feelings and thoughts, understand each other’s perspectives, and mutually agree on how to repair the harm.

- Mediation sessions: Mediation is used to address conflicts before they escalate. It involves a neutral third party who helps the disputing parties find a solution that is agreeable to all involved.

- Community service: Oftentimes, part of the resolution involves the offender engaging in community service, which serves both as a means of making amends and as a learning experience to foster better community relations.

- Restorative conferences: These are formal meetings that include not just the victim and the offender but also family members, school staff, or community representatives, depending on the context. The conference aims to work out how the offender can make amends and how the community can support the recovery process.

- Support and reintegration: Following an incident, there’s a focus on supporting both the victim and the offender. For the offender, the aim is to reintegrate them into the community or school, ensuring they have the support needed to avoid future conflicts.

The effectiveness of these practices depends on the commitment of all participants to the principles of honesty, respect, and mutual concern.

Restorative Justice Tier I: Prevention

The first tier is all about community building as a preventive measure. Teachers or peer facilitators can lead students in circles of sharing, where kids open up about their fears and goals. Students play an integral part in creating the climate of Tier I. The teacher and students start the year by creating a classroom-respect agreement. Everyone agrees to be held accountable. The contract is an extremely effective way of maintaining harmony in the classroom.

Restorative Justice Tier II: Intervention

Tier II comes into play when students break rules and someone has caused harm to someone else. In traditional justice, this is when punishments are meted out. Restorative justice instead turns to mediation. The offending student is given the chance to come forward and make things right. They meet with the affected parties and a mediator, usually a teacher.

The mediator asks nonjudgmental, restorative questions like What happened? How did it happen? and/or What can we do to make it right? Through their discussions, everyone learns about what happened, why it happened, and how the damage can be fixed.

Restorative Justice Tier III: Reintegration

Tier III aims to help kids who’ve been out of school due to suspension, expulsion, incarceration, or truancy. Returning to school life can be a real challenge in those cases. Many students in traditional environments quickly re-offend or drop out again. Restorative justice practices seek to reduce this recidivism by providing a supportive environment during re-entry from the start. They acknowledge the student’s challenges while promoting accountability and achievement.

Does restorative justice really work in the classroom?

Research shows that restorative justice “can be successful in schools because it creates interactional patterns that produce positive social-emotional outcomes like group solidarity and individual emotional energy. The social-emotional outcomes have implications for both individual students and entire school communities.”

In California, Oakland Unified School District began using the program at a failing middle school in 2006. Within three years, the pilot school saw an 87% decrease in suspensions, with a corresponding decrease in violence. The practice was so successful that by 2011, OUSD made restorative justice the new model for handling disciplinary problems.

“Implementing restorative justice led to a major culture shift in our schools—most powerfully, all faculty and students really began to connect and relate to each other as humans, rather than through the hierarchy of age and experience,” says Napleton. “Before we implemented restorative justice, that rapport existed in some parts of the building—but after working hard on restorative justice, it really permeated our entire web of relationships.”

Does restorative justice address racial justice?

OUSD’s Restorative and Racial Justice home page is clear: “There is no restorative justice without racial justice.” To begin with, this means honoring the roots of the practice. It also means encouraging program participants to consider how racial privilege and prejudice affect everyone.

The Center for Court Innovation runs restorative justice programs in five underserved Brooklyn schools. They’re trying to address the subject through a racial justice lens. “Restorative justice is about accountability and repairing harm,” they note. “What about accountability for the system that has produced these underserved and essentially segregated schools and then punishes the kids for reacting to that neglect?”

Dr. Sarah Davidon, senior policy advisor at Georgetown University School of Medicine and founder of Davidon Consulting, points out that exclusionary discipline (such as suspension or expulsion) is often “implemented disproportionately, with greater impact on Black students and students with disabilities, including mental health challenges.”

“Restorative justice can impact school culture in powerful ways, such as reduction in exclusionary discipline; schools often see dramatic drops in suspensions and expulsions, especially when restorative justice is implemented schoolwide,” explains Davidon. “It can improve school climate by encouraging empathy, accountability, and stronger relationships among students and staff. Students can learn to navigate problems constructively, which can support long-term social-emotional growth.”

One crucial step? “Monitor outcomes by race, gender, and disability status to ensure restorative justice is reducing and not reinforcing inequities,” says Davidon. “Data transparency is really key.”

Try these resources to learn more about this topic:

What are the potential benefits of restorative justice?

A major concern that some teachers may have when considering the implementation of restorative justice in the classroom is that it sounds like a lot of work. The truth is that it is a lot of work—especially when you’re just starting out. Like many things in life, though, the effort will be worth it.

Many teachers and administrators who use these programs say the benefits far outweigh the effort. Here are some potential positives of implementing restorative justice in the classroom:

- Improved behavior and reduced recidivism: Restorative justice practices focus on accountability and making amends, which helps students understand the impact of their actions. This approach has been shown to reduce repeat offenses and improve overall student behavior.

- Enhanced relationships: By promoting dialogue and mutual understanding, restorative justice fosters stronger relationships between students and teachers. This improved relational dynamic can lead to a more supportive and cohesive school community.

- Positive school climate: Implementing restorative practices helps create a more inclusive and respectful school culture. This environment is conducive to learning and personal growth, as students feel safer and more valued.

- Academic improvement: Schools that adopt restorative justice practices often see improvements in academic performance. This is partly because students who are not subjected to punitive measures like suspensions can spend more time in the classroom, engaging with their education.

- Conflict-resolution skills: Restorative practices teach students valuable conflict-resolution and communication skills. These skills not only help in school but also prepare students for constructive interactions in their personal and future professional lives.

These benefits highlight why many educators advocate for the implementation of restorative justice practices in schools as an effective alternative to traditional punitive discipline methods.

What are the drawbacks of restorative justice in schools?

For restorative justice to work, engagement from all involved parties is required. If the offender isn’t willing to take responsibility and make meaningful restitution, the program can’t help. Schools using this system find they still need traditional disciplinary actions available for circumstances like this.

More than this, restorative justice in schools requires a pledge of time and money from the district and its administration. There are multiple examples of schools that set aside funds to implement the program but leave the money unspent. Other districts encourage teachers to use restorative discipline but provide little or no training or support. And busy teachers are understandably leery of trying yet another program that’s supposed to solve all their problems.

On top of that, “leaders often significantly underestimate how much baggage every adult—teachers, staff, parents, etc.—brings to a conversation about consequences,” Napleton shares. “There are strong feelings about ‘how it should work’ and ‘back in my day,’ and when a school makes a shift towards a more repair-based approach, accusations of being ‘too soft’ are hurled. … We used to remark that everyone was on board with this idea until something happened to their kid—and they wanted the other student to be punished with a capital P.”

Schools that dedicate themselves fully to the system, like Oakland USD and Chicago Public Schools, see real change and benefits. But the time, money, and enthusiasm required to make it work can be prohibitive for others.

“To mitigate this, don’t be afraid to start small—with pilot programs or opt-in trainings for staff who are interested or lower-stakes elements of the discipline system,” says Napleton. “Identify what the hottest-button issues might be (like suspensions) and save those for year two or three of the work—don’t feel the need to take those on right away. Build some momentum with some wins.”

What do real educators think about restorative justice in schools?

When this topic pops up for debate in our We Are Teachers HELPLINE and Principal Life Facebook groups, educators tend to have a lot of opinions about it. Here are some of their thoughts:

- “We started RJ this year, and since it was so new, there was a STEEP learning curve for everyone involved, despite numerous trainings. Just remember that some students will respond to it right off the bat, some take time, and others are just not going to participate in circles and things, and that’s OK. My opinion is this: In theory, RJ is an excellent idea. I really think it can help build student-teacher relationships. In practice, the school must go ‘all in’ in order for it to work.”

- “I love this approach. It has been highly successful for me and my colleagues who took it seriously. I have seen improvements at tough schools that I’ve worked in. … By the way, this isn’t just for minority children. It isn’t just for Caucasian teachers. It’s for all people. These practices can also resolve issues with teacher and admin, parents and schools, etc.”

- “I find that many kids don’t open up in the circle and are afraid to share because the other kids don’t always respect what is said there. Not sure how to change that, but because they aren’t genuine in the circle, they are not reaping the benefits of genuine communication.”

- “Restorative justice cannot be rushed. It does not work when those participating have a time limit of 20 minutes and back to class.”

- “It takes time to build the culture. Have someone come in and give an overview of the philosophy and to share a circle. This gets everyone thinking. Don’t demand that everyone must do it … but request that everyone begins building relationships with their students and colleagues. Start with a team of teacher leaders who practice it and share their experience and celebrations. It will catch on! It takes about 3 years to build the culture!”

How can schools implement restorative justice?

In the classroom, teachers can use aspects of the restorative justice system, like respect agreements and sharing circles, to promote a healthy learning environment. Implementing school-wide restorative justice, however, can be a long-term process.

The Oakland USD provides a useful Restorative Justice whole-school Implementation Guide. Here are some streamlined strategies:

- Training and professional development: Provide comprehensive training for teachers, administrators, and staff on restorative justice principles and practices. Focus on facilitating restorative circles and managing constructive conversations.

- Restorative circles: Use restorative circles to build community and address conflicts, and implement conferences for more serious incidents. Both practices foster open dialogue and mutual understanding, ensuring collaborative resolution processes.

- Restorative conferences: Implement restorative conferences for more serious incidents. These involve structured meetings where the affected parties discuss the harm caused and work together to find ways to repair the damage and restore relationships. This approach ensures that all voices are heard and that the resolution process is collaborative.

- Peer mediation programs: Establish peer mediation programs where trained students help mediate conflicts between their peers. This not only empowers students to take an active role in conflict resolution but also promotes a culture of accountability and support within the student body.

- Policy integration: Integrate restorative practices into the school’s discipline policies. This means shifting from a punitive approach to one that focuses on repairing harm and restoring relationships. Clearly communicate this change to all stakeholders, including students, parents, and staff.

- Ongoing support and evaluation: Provide ongoing support for staff through regular training sessions, coaching, and access to resources. Additionally, regularly evaluate the effectiveness of restorative practices through surveys, interviews, and data analysis to make necessary adjustments and improvements.

- Community involvement: Engage the broader school community, including parents and local organizations, in restorative justice initiatives. This helps to create a supportive network that reinforces the values and practices of restorative justice beyond the school environment.

By following these steps, schools can create a more positive and inclusive environment that fosters healthy relationships and reduces conflicts, ultimately enhancing the overall school climate and student outcomes.

Expert advice for schools just starting out with restorative justice

Restorative justice shouldn’t be seen “as a quick fix,” advises Davidon. “Schools may find that restorative justice is too time-consuming or ‘soft.’ However, this can be guided through ongoing professional development and modeling restorative conversations among staff. Additionally, restorative justice loses effectiveness if it’s only used reactively or by a few staff members, so ensuring a school-wide approach is important.”

Napleton echoes this sentiment, noting that it can be especially tricky when it feels like students are “getting off the hook. Restorative justice properly implemented should never feel that way—it should feel like justice has been served—but that does sometimes take more creativity and ‘out of the box’ thinking than the old systems did. Ensuring the key leaders (principal, dean, etc.) share a brain on this and are totally aligned is critical.”

To facilitate this, take it slow. “Schools should be very intentional and not try to change the discipline system quickly,” says Davidon. “Beginning by embedding restorative conversations into everyday practices can help. Shift the culture through consistent practice, not big gestures of change. It’s so important to start by building trust among students and staff. Restorative justice won’t be very successful if the foundation is a school culture of mistrust.”

“Stay really connected to why you are doing this: Have a clear and vivid vision of what you want to be true and how that vision connects to the critically important work you do of preparing students to be good citizens and neighbors,” offers Napleton. “This process is guaranteed to have challenges, and remembering your why and the bigger picture will give you the fuel for the fire you need to keep moving toward that vision and through the messy middle of making this shift.

“You should also be able to narrate this vision—and its connections to the outside world, the school-to-prison pipeline, etc.—and engage your stakeholders in it so they understand the bigger why. Tapping into that in the emotional moments that inevitably come along will be important to keep people grounded in the bigger picture and helping them push through the more difficult moments.”

Additional Restorative Justice Resources

Institutes and Organizations

Books

Special Thanks

We’d like to extend a special thank-you to the following experts for sharing their time and insights for this article:

Beth Napleton, a coach and consultant who helps schools with change management initiatives like implementing restorative justice. Learn more at bethnapleton.com or connect with her on LinkedIn.

Dr. Sarah Davidon, senior policy advisor at Georgetown University School of Medicine and founder of Davidon Consulting, where she supports schools, agencies, and organizations in improving policies and practices around children’s mental health. Learn more at davidonconsulting.com or connect with her on LinkedIn.

Get your free behavior reflection sheets!

Designate a reflection center (usually just a quiet spot within the classroom) where students can fill out these behavior reflection sheets. It’s an opportunity for them to reflect on their behavior, whom it affected, and what they could do differently next time. Just click the button below to get your free worksheets.

Does your school use restorative justice or are you looking to start? Come join the We Are Teachers HELPLINE group on Facebook and chat with other teachers about your experiences.

Plus, check out our guide What Is Classroom Management?