About a decade ago, leaders at the Kentucky Department of Education set out to develop guidelines for what quality math instruction should looked like in the state, convening educators from the general education and special education teams at the agency.

But those two groups found themselves at odds over one key issue: encouraging “productive struggle.”

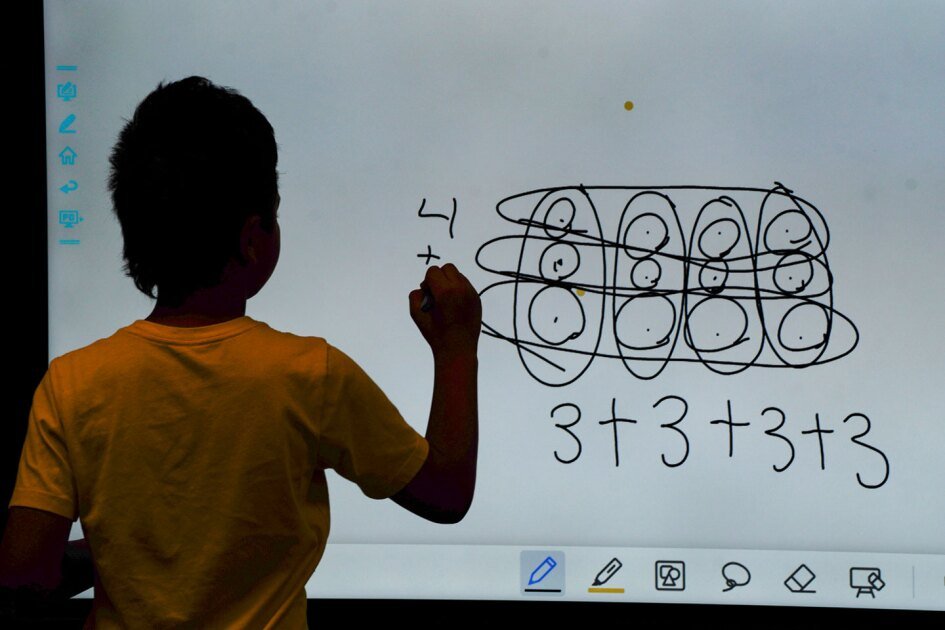

Math leaders wanted to include the approach, in which teachers present students with challenging, open-ended questions that prompt them to grapple with mathematical ideas and persevere to solve problems. But special educators were hesitant, said Amanda Waldroup, the assistant director of the division of Individuals with Disabilities Education Act implementation and preschool in the Kentucky education department’s office of special education and early learning.

“They were worried that it would create frustration for students,” Waldroup said.

This back-and-forth in Kentucky might seem like a small disagreement, but it’s representative of a broad gap between how general educators and special educators understand what good math teaching looks like. And it’s a tension that reverberates throughout math education policy, since states such as California and major math education groups have embraced inquiry-based math education.

A new paper that examines the tension argues that teachers need proven strategies to serve students with disabilities and those who struggle in math—and the divide between general education and special education makes it less likely they’ll get access to them. What’s more, its authors say, the root of the problem lies in differences in how these groups of teachers are trained.

“To us, it was really clear that this starts within colleges and universities, but has widespread implications,” said Nathan Jones, an associate professor in special education at Boston University and one of the authors of the paper. (He is currently on leave as the commissioner of the Institute of Education Sciences’ National Center for Special Education Research.)

Researchers disagree over teachers’ role in student learning

It might seem reasonable that there’s a difference between general and special ed. in terms of what teachers are taught about best practices. Students with math disabilities, after all, have some unique needs, frequently needing more help with developing number sense and place value. But most general education teachers have some students with disabilities in the classrooms, and nearly all of them will teach kids who are struggling in math.

The study, from researchers at the University of Virginia, Boston University, and the University of Delaware, catalogs the similarities and differences between how researchers in general education and special education conceptualize the goals of math education and the roles teachers should play. Jones and his colleagues Julie Cohen and Lynsey Gibbons drew on a series of structured interviews with 22 prominent academics, 11 each in special ed. and general math education.

They asked the researchers what they thought math teaching and learning should look like, covering big themes—like what knowledge and skills should take center stage, what the role of the teacher is in the classroom, or what “success” means in math—as well as specific topics that have become flashpoints in the math field, such as the role of productive struggle, or guided practice.

Both groups agreed that students needed to develop deep conceptual understanding of math topics, and that teachers needed to differentiate instruction to serve all learners. But they differed in their perspectives on how educators could best achieve these ends, and at some level about the very purpose of the subject itself.

Special educators tended to focus on what the authors called “school-based” goals. Success in math could be measured by data-based outcomes like mastering standards, or being prepared for more advanced courses in high school and college. General math ed. researchers, in contrast, focused on broader goals, like finding “joy” in math, or using it to engage in civic life.

“Special educators framed their goals based on the world as it is, pushing for change, but without necessarily challenging the status quo structure of K–12 schools,” the researchers wrote. “General educators, by contrast, more often proposed radical change to that status quo, underscoring ideas about the world as it should be and proposing goals to reimagine why we learn mathematics.”

The groups also diverged in what role they expected teachers to take in student learning.

The math general education researchers prioritized inquiry, arguing that classrooms should be weighted toward student discourse over teacher-directed instruction, and that students should try tackling problems first before teachers modeled how to solve them.

Special education researchers said the process should happen in the opposite order: Teachers should use explicit instruction to break down complicated processes first, guide them through examples, and then give students the opportunity to try challenging problems.

This tension between explicit instruction and a more inquiry-based approach is one of the issues at the heart of the ongoing “math wars,” a decades-long debate about the best way to teach the subject that’s waxed and waned through the years.

How do divides in math teaching methods show up in classrooms?

There are several ways these divides show up in the classroom.

“The high-quality instructional materials that are being rolled out across the country, a lot of those programs really privilege inquiry approaches and discourse-heavy pedagogy,” said Julie Cohen, an associate professor of education at the University of Virginia who studies teacher quality and evaluation, and the lead author on the study.

Such programs can still be effective for students who struggle in math, but the instructional techniques researched in special education could help “scaffold kids and support them,” she said. Some of those techniques feature more explicit, step-by-step teaching to guide students’ mathematical reasoning—a technique that’s proven to help students who need more support in the subject.

But, Cohen said, “it was just so clear in the research we did for this paper that the most prominent math education researchers in this country were pushing back against this idea.”

General education researchers mostly “did not demonstrate familiarity with mathematics-related disabilities,” the study’s authors wrote.

For their part, special ed. researchers also weren’t fluent in some of the issues that math general education researchers studied—like the effect of bias on students’ math achievement and self-perception.

“Special educators were using a lot of deficit language,” Cohen said, for example, talking about students’ use of “immature” strategies. They didn’t usually discuss how social factors, like race and power, could influence classroom dynamics and shape whether kids saw themselves as math people.

“The way we talk about kids and their ideas, and their strategies, and the way that they approach math, I think those things really do matter,” Cohen said.

A larger battle over ‘evidence based’ math instruction

Back in Kentucky, the general and special ed. leaders eventually found consensus on “productive struggle,” said Waldroup of the state department of education.

They kept the recommendation, but qualified it, noting that teachers should prompt students with strategic questions to ensure students keep moving forward. “A lot of that revolved around how you do it, so that it doesn’t create frustration for the students,” Waldroup said.

How schools do, and should, define best practice is an especially salient topic now. Several states have passed legislation requiring that schools screen students for math difficulties and intervene early. Some, including Alabama and Indiana, specify that these tools and approaches should be “evidence based.”

But with two competing research literatures, the field is still fighting over the definition of “evidence based.”

In 2024, the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics and the Council for Exceptional Children—professional organizations for math teachers and special education teachers, respectively—put out a joint statement in an attempt to reach common ground.

The document said students with disabilities “have a right to high-quality instruction” and should be “provided with appropriate supports.” It included a list of high-level recommendations, including that teachers “position students with disabilities as valuable owners of and contributors to the mathematics being learned,” and “build meaningful connections between concepts and procedures.”

In response, more than 30 special education researchers signed a letter arguing that many of the recommendations were “merely beliefs and philosophies without significant and rigorous research to support them.”

The joint statement from NCTM and CEC didn’t emphasize systematic, explicit instruction, a decision that letter writers called “educational malpractice” given its strong research base in supporting students with disabilities.

The episode underscores the challenges inherent in this kind of collaboration, said Jones. “It is much easier to come to consensus on making instruction accessible, and [saying] everyone belongs,” he said. “It is much harder to put pen to paper and say, we agree on these practices.”

One group of special education researchers has planted a flag, launching the “science of math” in 2021—a movement modeled after the “science of reading,” making the argument that a similar focus on systematic, explicit instruction and guided practice is necessary in both subjects for students to develop foundational knowledge. It rejects the inquiry-based methods promoted by professional organizations like NCTM.

But a “science of reading” framework might not map as easily onto math, in part because there isn’t quite as large of a body of research, said Jones.

“I think we want to avoid the scenario with other subjects where we have winners and losers in a way that is not always helpful. I think we have this opportunity with math,” he said.

If there’s anything to emulate from the science of reading movement, though, he said, “it’s planning with the marginalized student in mind. It’s instruction with those students at the center.”