The Rev. Jesse L. Jackson, a protege of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and two-time presidential candidate who led the Civil Rights Movement for decades after the revered leader’s assassination, died Tuesday. He was 84.

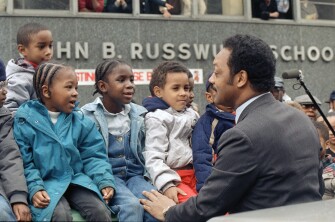

Jackson throughout his career pushed for more equitable forms of public school aid for impoverished communities.

He also argued that increased support for education programs was essential in creating opportunities for young people who might otherwise end up in the criminal justice system.

As a young organizer in Chicago, Jackson was called to meet with King at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tenn., shortly before King was killed, and he publicly positioned himself thereafter as King’s successor.

Santita Jackson confirmed that her father, who had a rare neurological disorder, died at home in Chicago, surrounded by family.

Jackson led a lifetime of crusades in the United States and abroad, advocating for the poor and underrepresented on issues from voting rights and job opportunities to education and health care.

He scored diplomatic victories with world leaders, and through his Rainbow/PUSH Coalition, he channeled cries for Black pride and self-determination into corporate boardrooms, pressuring executives to make America a more open and equitable society.

And when he declared, “I am Somebody,” in a poem he often repeated, he sought to reach people of all colors. “I may be poor, but I am Somebody; I may be young; but I am Somebody; I may be on welfare, but I am Somebody,” Jackson intoned.

It was a message he took literally and personally, having risen from obscurity in the segregated South to become America’s best-known civil rights activist since King.

“Our father was a servant leader—not only to our family, but to the oppressed, the voiceless, and the overlooked around the world,” the Jackson family said in a statement posted online. “We shared him with the world, and in return, the world became part of our extended family.”

During a 1995 address at the annual convention of the National Education Association, the nation’s largest teachers’ union, Jackson called for strong character education as a strategy to boost faith in public schools. He argued that educators had ceded ground on the issue to the political right.

“Parents want their children to be safe in schools and learn the basics,” said Jackson, as reported by Education Week. “And they will desert the public schools if they are concerned that they aren’t. We can’t take their support for granted.”

A few years later, during a conference in Chicago, Jackson said that the cost of incarcerating inmates was higher than the amount spent per-pupil in the Chicago school system.

He described a then-new, maximum-security prison in the community as “an extension of our failed school system.”

“Everything that should be in our schools is in our jails,” Jackson said during a tour of the facility.

He also maintained that public schools’ reliance on property taxes, as opposed to other forms of revenue, worsened inequities across communities.

“When I was growing up in Greenville, South Carolina, the gap based on race, as bad as it was, was not as severe as the one now based on the property tax,” he said. “While there’s clearly a black-white division, there is a have/have-not polarization that is even more pronounced.”

Jackson shepherded a number of efforts to reduce school violence. He toured schools and asked students to sign a pledge committing to take steps to curb violence and drug use on their campuses.

Despite profound health challenges in his final years, Jackson continued protesting against racial injustice into the era of Black Lives Matter. In 2024, he appeared at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago and at a City Council meeting to show support for a resolution backing a ceasefire in the Israel-Hamas war.

“Even if we win,” he told marchers in Minneapolis before the officer whose knee kept George Floyd from breathing was convicted of murder, “it’s relief, not victory. They’re still killing our people. Stop the violence, save the children. Keep hope alive.”

Jackson had his share of critics, both within and outside of the Black community. Some considered him a grandstander, too eager to seek out the spotlight.

Looking back on his life and legacy, Jackson told The Associated Press in 2011 that he felt blessed to be able to continue the service of other leaders before him and to lay a foundation for those to come.

“A part of our life’s work was to tear down walls and build bridges, and in a half century of work, we’ve basically torn down walls,” Jackson said. “Sometimes when you tear down walls, you’re scarred by falling debris, but your mission is to open up holes so others behind you can run through.”

He worked as an aide to Martin Luther King, Jr.

Jesse Louis Jackson was born on Oct. 8, 1941, in Greenville, S.C., the son of high school student Helen Burns and Noah Louis Robinson, a married man who lived next door. Jackson was later adopted by Charles Henry Jackson, who married his mother.

Jackson was a star quarterback on the football team at Sterling High School in Greenville, and accepted a football scholarship from the University of Illinois. But after he reportedly was told Black people couldn’t play quarterback, he transferred to North Carolina A&T in Greensboro, where he became the first-string quarterback, an honor student in sociology and economics, and student body president.

Arriving on the historically Black campus in 1960 just months after students there launched sit-ins at a whites-only lunch counter, Jackson immersed himself in the blossoming Civil Rights Movement.

By 1965, he joined the voting rights march King led from Selma to Montgomery, Ala. King dispatched him to Chicago to launch Operation Breadbasket, a Southern Christian Leadership Conference effort to pressure companies to hire Black workers.

Jackson called his time with King “a phenomenal four years of work.”

Jackson was with King on April 4, 1968, when the civil rights leader was slain. Jackson’s account of the assassination was that King died in his arms.

As presidential candidate he sought to “redefine what was possible”

Despite once telling a Black audience he would not run for president “because white people are incapable of appreciating me,” Jackson ran twice and did better than any Black politician had before President Barack Obama.

He won13 primaries and caucuses for the Democratic nomination in 1988, four years after his first failed attempt.

His successes left supporters chanting another Jackson slogan, “Keep Hope Alive.”

“I was able to run for the presidency twice and redefine what was possible; it raised the lid for women and other people of color,” he told the AP. “Part of my job was to sow seeds of the possibilities.”

U.S. Rep. John Lewis said during a 1988 C-SPAN interview that Jackson’s two runs for the Democratic nomination “opened some doors that some minority person will be able to walk through and become president.”